Language, Communication, and Power between BIPOCs and PWIs in the American Theater

Cycle 1 of PANTHER WOMEN | Photo By Jennifer Hearn

The late, great, Maya Angelou once said “words are things. Some day we will be able to measure the power of words. The power of language.” And indeed, I agree! Often times when we think on language and communication, we, as an American culture, tend to think of words and how they affect people on a very narrow level. Just because we may all speak English, does not mean that we speak the same English. Perhaps you may not understand the ideology behind my thoughts? Since at this moment, you are reading this essay which I have written, I have the power. I am controlling the narrative of this essay. And since I have the power it is my duty and responsibility to try to expound to you, in the clearest way possible, my paradigms on this topic. And if maybe our denotations do not align, then we might consider creating our own unique language and way to communicate. It is the job of the person who is in power to create an environment where communication is clear. And just like the macrocosm of America, in the very microcosmic world of The American Theatre, white men have most of the power.

In the last few years, many predominately white American theatres have been attempting to move towards a more equitable, diverse, and inclusive habitat within their institutions. From my vantage point, as an African American, woman, theatre-maker, I’ve concluded that most predominantly white organizations focus on the emotional response of people of color, and how not to cause harm to BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) artist individuals, when we are given space in their theatres. Though these are wonderful points, it seems that PWI’s (predominantly white institutions) are more focused on results, or on a situation that might occur before it actually has, rather than what is actually happening in that present moment. Nonetheless, I do believe that precautions should be made and put into consideration. However, I also believe, for example, that what this kind of thinking can create is a path to PWI’s confusing the idea of speaking to BIPOC artists in a polite and respectful manner with the final factor in effective communication, as opposed to putting emphasis on whether the individual is actually understanding what they’re hearing from you. Placing things in the moment/in the present can lead closer to understanding in transactional moments between two individuals who might, culturally and academically, have separate lived experiences.

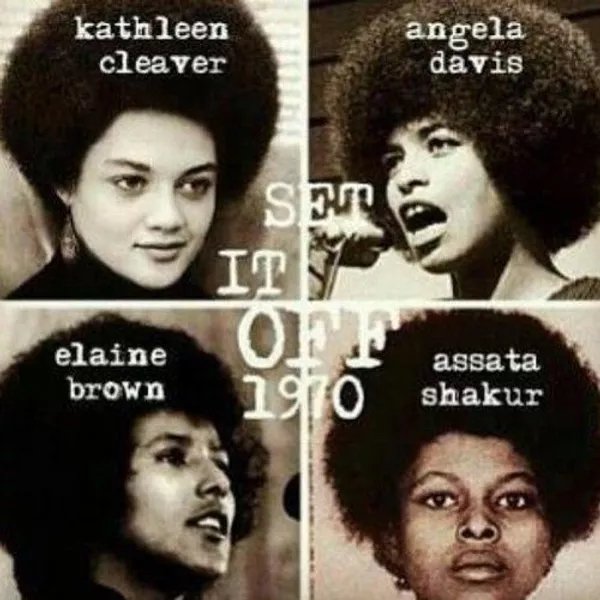

A photo Burton keeps hanging in any space where she writes PANTHER WOMEN. She says, "Gives me the motivation to go on. Kathleen Cleaver, Angela Davis, Elaine Brown and Assata Shakur. These are pioneers of the Black Liberation movement."

On the other hand, in preparing to understand or making sure that the individuals whom you are inviting into your space feel heard and seen, and to reduce the possibility of confusion and miscommunication, white theatres must diversify their staff. When asking BIPOC or BIPOC communities to share their personal stories, to be vulnerable, it is most certainly important to exemplify representation of people of color within that institution. Not to say that this is the ultimate remedy to eliminate barriers between two different cultures and groups of individuals indefinitely. However, there is a certain familiarity and comfort in recognizing someone who looks like you that might allow more room for comprehension among both parties. It can be most uncomfortable sitting in a room of white people talking about inclusion, diversity, and equity, when you’re the only person of color in that room. I know on a first-hand basis what it feels like to be in those rooms. It is certainly not the person of color's responsibility to teach PWIs how to be comfortable hiring staff that may not share the same beliefs, values, or cultural backgrounds. It is most disappointing and demoralizing to have to carry that kind of weight. It leaves too much of the responsibility on the single person of color in that room. Black people are not monolithic: I cannot be the voice of all Black people, just as I cannot be the voice of all women and LGBTQ+ individuals. These are all a part of the make-up of who I am, but even I am hesitant to speak about my humanity when what is being reflected back to me is a series of white faces. When there isn’t adequate representation of people of color helping to make decisions in that institution, it lessens the opportunity of the BIPOC group to speak freely about their wants, needs, and aspirations during their tenure at that PWI.

It is important that PWIs do not try to project their ideology or paradigms of what they believe “good theatre” is or is not. As the American Theatre moves towards a more communal way of creating theatre (devised theatre), seeking marginalized stories, and finding a way to work with artists of color and also non-artists of color, you must understand that you have been indoctrinated, washed in the blood, doused in and put-upon, aka “trained,” to believe that the “right way” to do theatre is the way of the white patriarchal structure, created by European practitioners. We learn in college that the first people to record and conceptualize theatre were the Greeks, that Henrik Ibsen is the Godfather of modern drama, we are trained in Stanislavski, Meyerhold, and Meisner techniques. It is hard to undo what has been beaten into your head for years. Even I as an African American Woman, who has gone to college for theatre, struggle with breaking away from the conventional traditions of theatre and its influencers. The jargon and language we are taught in our education can create a barricade between you and the individuals that you are working with.

Though individuals of color attend colleges and receive formal training in theatre arts, the majority of non-whites in America lack access to that kind of training in any form or genre of art. This all must be considered before going into a rehearsal room, and pertains to but is not limited to non-traditional artists. For example:

I can recall going into my first audition outside of high school, in which we did not have a theatre arts program. We were merely taught some songs from a musical by our music teacher and were expected to go onstage and figure it out. My two friends, who were also African American, accompanied me to the audition. We all went to the same high school and grew up in the same area of town together. When we walked into the room and looked around, we saw a conundrum of white teenage faces glaring at us. It was clear that most of these kids had formal training by the way they were warming up. My friends and I were the only Black people. The audition team was all white, too. This made us even more nervous than we already were. For at this moment in our lives, we had never been in a room with this many white people. We were the majority at our school and in our neighborhoods. My friend whispered to me “Are you sure we belong here?”

The director immediately asked everyone to put on jazz shoes; my friends and I looked at each other in confusion. We had never heard of such a thing in our lives. The director saw that we didn’t have any, so he simply told us to work barefoot. As he taught the song and choreography, he kept giving us all instructions to “go stage right, now upstage, do a jazz square...” etc. My friends and I had never gone to a theatre class or had training in dancing in our lives. “Ok, now next we are going to look at each of your prepared monologues,” he said. My friend whispered to me, “What’s a monologue?” I shrugged my shoulders. Then, the director, who was already physically showing his annoyance with us, asked us did we have a prepared monologue? We said no. He then responded, “Very well, then we will have to do a cold read.” “A cold read?” I thought. “Is that some kind of sandwich?” My friends laughed. I was first. I read the monologue and then I was done. I was proud of myself for getting through it. He then stopped me and said, “Now do it over and think about the exposition, think about her objectives, and what tactics she uses to get them.” I didn’t understand the lingo, however, I did it again. I felt like I did it differently, but then again, I had no idea what I was supposed to do. Needless to say, none of us receive a part. That moment, for me, solidified my thoughts about what white people thought of us - not just what white people thought of us, but also what we were always being told by the Black people around us “You’re going to have to work harder than white people. You have to be two to three times better than they are to even get looked at.” My friends never did theatre again. I, on the other hand, went to college and learned what tactics, objectives, and exposition meant.

A few years after I graduated from college, I was called to devise a piece with a group of African American young girls and boys, about their lives and experiences in a detention center. On the first day of rehearsal, I started throwing out those same words to these underserved children who were barely surviving, let alone having the access or time to go to a theatre camp or performing arts school. I thought that teaching them the “universal" language of theatre would only help them; however, it made them feel disconnected from me. I was running my rehearsals like they had been performing for their entire lives. I created a completely toxic environment. The most disheartening thing for me, looking back, was that even after that experience, I didn’t think I was doing anything wrong; I was teaching them “the right way” to communicate in a rehearsal setting.

Burton and Andrea Belser-McCormick in rehearsal for Cycle 2 of PANTHER WOMEN | Photo by Jennifer Hearn

It wasn’t until I started devising my latest piece, Panther Women: An Army for the Liberation, in 2018 that I started to understand that I had to gain these actors' trust. That just because I was a Black woman didn’t mean they were going to come in and just start spilling their guts. We were rehearsing in a predominately white institution, that I knew might want to produce the show someday as a full production. I had to listen to them. Not come in with any expectation, but to meet them where they were. And that is what I did. Some of them had never devised a play in their lives. It took a lot of patience, failures, and triumphs for me to understand who I need in the room with me, and how I was supposed to be in the room with the actors.

Do not be afraid to ask questions, however, think about how to phrase those questions. Often times it’s not what you say, but how you say it. You could say the same thing to a white person and a person of color, and it could mean something completely different. White theatre leaders, it is also ok to settle with the idea that you might not ever understand a specific cultural language or be able to infiltrate that commonality that the specific group shares; this does not mean you give up. Create and talk about expectations together, create a contract of boundaries, so that you and the individuals you are working with have an agreement to hold each other accountable. This idea is imperative because if you create the rules and language together, then it becomes less of a dictatorship and more of a democracy.

Accept these ideas and perhaps some of the power you possess can be allocated to BIPOC artists who don’t struggle with understanding a specific group of individuals. Allowing marginalized groups, especially those who are non-traditional artists, to take part in the development of expectations can also lead the way towards trust. White theatre leaders, it is ok to allow yourselves to feel uncomfortable, for there, in that moment where you finally feel excluded, is where the listening and understanding are most alive and potent, where you learn the most, where the beauty of the communion of theatre and humanity exists.

In my farewell, I leave you with the idea that the only way to truly dismantle white supremacy within your organization is to practice radical policy change. This might mean completely abandoning the infrastructure in which you operate now, and creating a new one. Though this may be easier said than done, no revolution has ever been successful without radicalization, without courage or bravery. And to make sure that this revolution is not attempted in vain, invite some other people to the table who may not speak the same language that you are comfortable hearing. And, listen to them!

This is a legacy photo paying homage to Cleveland women artists taken during Cycle 2 of PANTHER WOMEN. You can see just some of Cleveland’s African American Women Theatre Artist, Poets, Dancers, Actresses and creators form ages 11-70. Photo by Jennifer Hearn

All photos are related to Burton's work Panther Women: An Army for the Liberation, and are provided courtesy of the author.